Plantations could be used to teach about US slavery if stories are told truthfully

Plantations could be used to teach about US slavery if stories are told truthfully

Amy Potter, Georgia Southern University and Derek H. Alderman, University of Tennessee

State legislatures across the United States are cracking down on discussions of race and racism in the classroom. School boards are attempting to ban books that deal with difficult histories. Lawmakers are targeting initiatives that promote diversity, equity and inclusion in higher education.

Such efforts raise questions about whether students in the U.S. will ever be able to engage in free and meaningful discussions about the history of slavery in America and the effect it had on the nation.

As cultural geographers, we see a potential venue for these kinds of discussions that we believe to be an overlooked and poorly used resource: plantation museums.

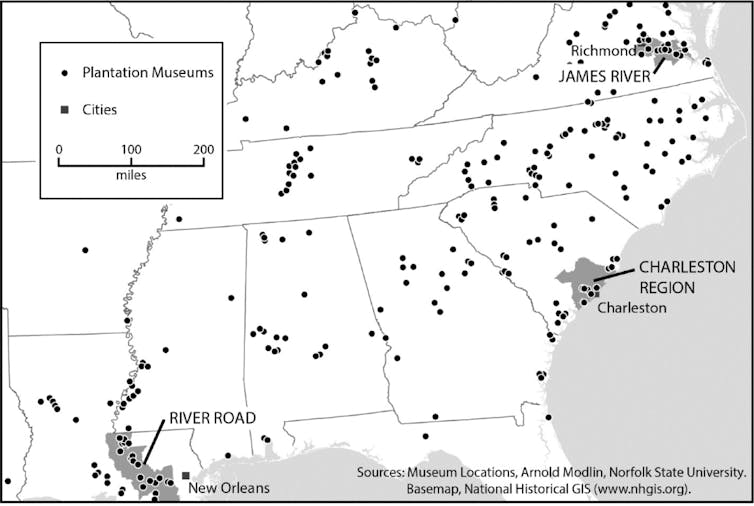

If slavery is, as historian Ira Berlin argues, “ground zero for race relations,” then the hundreds of plantation museums that dot the southeastern U.S. landscape seem like natural places to confront the difficult history of America’s slave-owning past.

Exploring that possibility is one of the reasons why – along with fellow tourism scholars Stephen Hanna, Perry Carter, Candace Bright and David Butler – we received a federal grant to research plantation museums across the U.S. South.

We think these plantation museums could be important sites for an educational reckoning with this difficult aspect of America’s past. But that’s only if the people who run these museums are committed to telling the truth about what took place, rather than perpetuating myths about Black life in America under white domination and oppression. This is particularly important as policymakers seek to curtail discussions about racism – or even themes that make people feel “discomfort” – in America’s K-12 schools and colleges and universities.

Usages of these sites have traditionally romanticized life before the Civil War and ignored or trivialized the horrors of slavery. They have also downplayed the resistance and resilience of enslaved communities, thus preventing the nation from getting a fuller and more accurate picture of American slavery.

Reforms needed

In order to make better use of plantation museums as places to learn about racism and slavery, the museums must be reformed in a major way and do more than just entertain tourists and sell a heritage experience. Rather, this reform demands a reworking of almost every facet of the museum – from misguided tours that gloss over the harsh living conditions of the enslaved to artifacts and marketing materials that emphasize the opulent and picturesque mansions that belie the horrors of what took place on the surrounding grounds. In our research, we discovered plantation museums where 50% of the tours never mentioned slavery. Our work provides practical guidance to the changes that need to happen.

Problematic places of learning

Within the United States, there are at least 375 plantations open for public tours scattered across 19 states. Based on nearly 2,000 surveys our research team conducted, visitors have indicated that they go to plantations to “learn about history.” The general public considers historical sites, such as plantation museums, to be trusted sources for historical information. Therefore, they deserve to be held accountable for the educational experience they provide.

School field trips are an important revenue source for these often cash-strapped sites.

At Shirley Plantation in Virginia, field trips accounted for over 15% of total visitors. At Meadow Farm, near Richmond, Virginia, 40% of the site’s visitors are school children. At Boone Hall in South Carolina, 14,000 school children visit the site annually.

Whitewashing of history

At one Virginia plantation museum, we observed school children go on scavenger hunts where they take on the roles of white slave owners. In one case, the children deliver a message between the white slave owner’s son – a Confederate soldier – and his sick mother while their plantation was occupied by Union troops. This, we believe, leads the children to identify and empathize with the white slave-owning family as opposed to the individuals they enslaved.

Toward reparative education

Our work calls for plantation museums to engage in a more reparative form of education. This education would come to terms with the injustices of the past and correct the way enslavement is actively misremembered in the present, which in turn harms Black well-being and sense of belonging.

Repairing these historical fallacies is not just about getting the facts correct about the enslaved and the enslavers. It also requires the public to learn certain emotional and social truths about how slavery is a source of pain and tension in America. Lessons should show how this tension continues to impact race relations. Often overlooked is how enslaved labor was used to construct buildings, roads, ports and rail lines we use in America.

Our research found that many plantation museums were reluctant to highlight Black lives and histories. But there is promising evidence of change at sites like McLeod Plantation on James Island in Charleston, South Carolina, which opened in 2015, less than a year after the more well-known Whitney Plantation in Louisiana.

We see both museums – Whitney and McLeod – as exceptional in plantation tourism. Combined, our research found these two sites attract a more racially diverse visitorship than many other plantations because of the inclusive stories being told. Our surveys with visitors suggest public interest in the topic of slavery increased after taking guided tours that focused on the experiences of enslaved communities. In our view, this is a needed counterpoint to media reports of some visitors pushing back against hearing these sober discussions. For instance, tour guides at McLeod reported white visitors yelling at them, claiming the tour attacked their ancestors.

Both of these plantations represent a new way of educating the public about the realities of slavery. Here are three things that stood out during our assessment of the Whitney and McLeod plantations.

1. They incorporate slavery and the lives of the enslaved throughout the tour

We think it’s important to feature slavery and the lives of the enslaved during all aspects of the tour and not keep it separate in a special exhibit.

Visitors should be given an opportunity to make thoughtful connections to those who were once enslaved by learning names and details about their lives. At Whitney, for example, visitors are encouraged to make emotional connections. One way they do this is by receiving a lanyard at the start of the tour that features the words and image of a formerly enslaved child.

2. They provide visitors a space to contemplate

We know the plantation can be an especially fraught and emotional experience, particularly for Black visitors. During our fieldwork, Black visitors would often describe the land as sacred and a powerful place to connect to the ancestors. Some of these plantations have even hosted Black family reunions. Whitney Plantation provides opportunities for visitor reflection and contemplation throughout the tour, such as benches near a wall that memorializes and honors all of the people who were enslaved there.

3. Tour guides were well prepared

Amy Potter, CC BY

McLeod’s management purposely hired guides who would disrupt romantic notions of the plantation and engage meaningfully with themes of slavery, race and social justice. They also provided ongoing training and support to guides doing the difficult work of challenging or complicating long-held plantation myths.

[Over 150,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Managers at McLeod acknowledged the stress experienced by their tour guides when they focused on enslavement and its aftermath. They took extra steps to ensure that their guides were supported by initiating a “golden hour.” This was a time for staff to come together and reflect on difficult encounters with the visitors, who sometimes challenged guides’ historical knowledge and fairness. It was also a time for the guides to develop strategies to cope with the emotional toll of the hostility they faced while doing their jobs.

Amy Potter, Associate Professor of Geography, Georgia Southern University and Derek H. Alderman, Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.