UT Geographers Put GIS on the Map at Statewide Meeting

UT Department of Geography and Sustainability faculty, students, and staff represented Vol geography in a huge way at the annual Tennessee Geographic Information Council (TNGIC) Conference for geospatial professionals April 9–11, 2024, at Montgomery Bell State Park, in Burns, Tennessee, west of Nashville.

Michael Camponovo, director of both UT’s GIS outreach and the GIST Program, was conference chair. A host of Vol geographers led workshops, gave presentations, and earned awards during the conference.

“As a student, TNGIC gave me the opportunity to create and share maps, give presentations, and build the professional network that eventually led to my job here at UT,” said Camponovo. “As a GIS professional, I want my students and alumni to have these same opportunities to launch their careers. That’s why I’m so passionate about getting involved with TNGIC.”

The TNGIC works to improve connections among agencies working with geographic information systems (GIS) in Tennessee. Their annual conference offers opportunities for GIS professionals and students to network, learn, and share their work and new ideas in the field. Keynote addresses at the conference were delivered by Budhendra Bhaduri, director of the Geospatial Science and Human Security Division at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, and Nikolas Smilovsky, geospatial solutions director at Bad Elf, a global navigation satellite systems company.

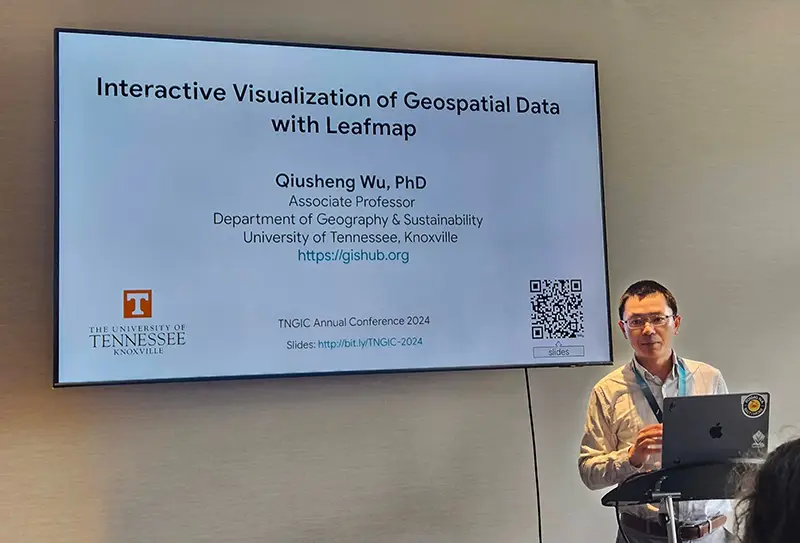

Associate Professor Qiusheng Wu led a workshop focused on cloud computing with Google Earth Engine and Geemap and presented with the FOSS (open-source GIS) community on Leafmap and data visualization. Wu also organized the inaugural TNView Remote Sensing Presentation Contest for students.

Lecturer Mayra Roman-Rivera and Professor Derek Alderman shared the work their students are doing as part of the GEOG 420—GIS in the Community class.

UT’s GIS Lab Manager Tim Kane volunteered with the UT cemetery mapping team to collect terrestrial lidar as part of a service project at Montgomery Bell State Park.

Student Caroline Petersen earned first place in the conference mapping contest, best analysis category, for her research using MaxEnt for pollinator prediction in Davidson County. She and fellow Vol Josiah Cubol were selected to join the TNGIC Outreach committee.

Emma Blanks and her team from GEOG 420 earned the Viewer’s Choice award in the map gallery for their work on the revised Tennessee Atlas. Blanks also gave a presentation highlighting how she and her team used ESRI’s Experience Builder to create the interactive Tennessee Atlas.

Mahnaz Meem won third place in the inaugural TNView Student Remote Sensing Presentation Contest. Cam Corsino presented a fascinating, in-depth storymap focusing on Knoxville’s Red Summer.

In a less GIS-specific activity at the conference, Ben Pedersen and recent alumnus Robby Lape won first place out of 32 teams at the 2024 cornhole tournament. They took home brand new cornhole boards as prizes.

“I hope anyone interested in learning more about GIS and geospatial technology will join us for future TNGIC events,” said Camponovo. “It’s a great way to learn about new technologies and workflows, meet alumni and network, and learn about jobs. Between presenting, submitting maps and posters, leading workshops, serving as business partners, and more, there are many ways for students and alumni to engage with the organization.”

Interested geographers can participate in the free, one-day East Regional Fall Forum in Johnson City (ETSU) on Tuesday October 15, 2024. The next annual meeting will be at the Embassy Suites in Murfreesboro April 15–17, 2025.

The geography department thanks the dozens of Vol alumni who attended the conference and made current students feel welcome within the organization:

- Danielle (Dami) McClanahan organized the cornhole tournament and was elected to the TNGIC board of directors.

- Tracy Homer shared her expertise with the FOSS community on creating art from digital mapping products.

- Caitlyn Mills presented her work with Stantec for the Tennessee Department of Transportation.

- Paul Dudley served as the TNGIC president over the last year and presented on his project of mapping all the trails in Tennessee. He was also instrumental in organizing our very first “Nerf war.”

- Kurt Butefish of the Tennessee Geographic Alliance provided an update on K–12 geography education in Tennessee and was a business partner for the conference.

- Danielle McClanahan, Caitlyn Mills, and Bass Neal from Stantec were also business partners at this year’s conference.

- Tracy Homer designed and created the Tennessee Rivers laser cut map that was the grand prize for our door prizes.

- Sam McCloud, Caelan Evans, and Danielle McClanahan were instrumental in organizing the conference.