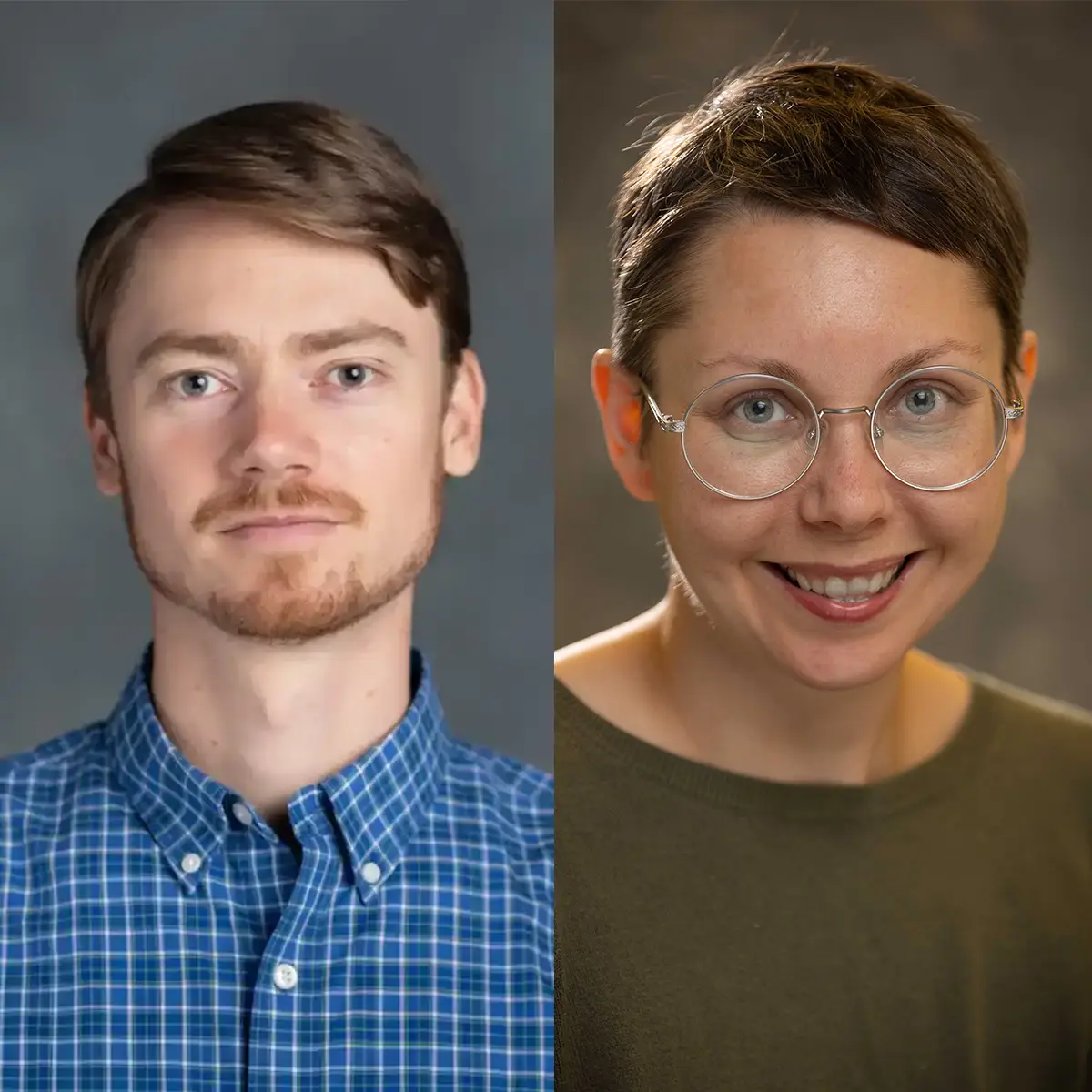

Schwartzman and Shade Map Economic Opportunity in Appalachia

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) awarded a planning grant of just over $389,000 to UT Assistant Professor Gabe Schwartzman, Department of Geography and Sustainability, and incoming Assistant Professor Lindsay Shade, Department of Sociology, to help create and improve geographical information system (GIS) services for rural counties in Appalachia. This important project will help provide valuable information for post-coal industry economic development throughout Appalachia.

The grant is part of ARC’s Appalachian Regional Initiative for Stronger Economies (ARISE) program, a $1.7 million investment of grants to develop workforce capacity plans in key industries in Appalachia. In addition to GIS development, these include cybersecurity, infrastructure, and housing.

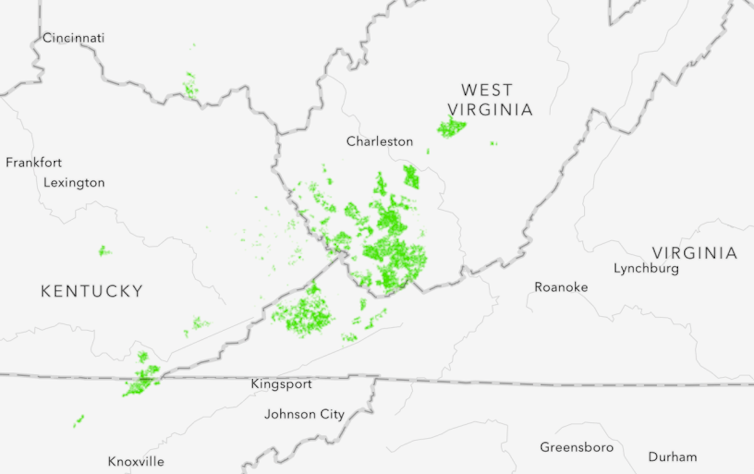

“Better equipping counties in Central Appalachia with geospatial technology can help these communities adapt to a changing fiscal landscape, and a future without coal-based revenue,” said Schwartzman.

Added support from the University of Tennessee and other regional partners brings total funding for the project to more than $489,000.

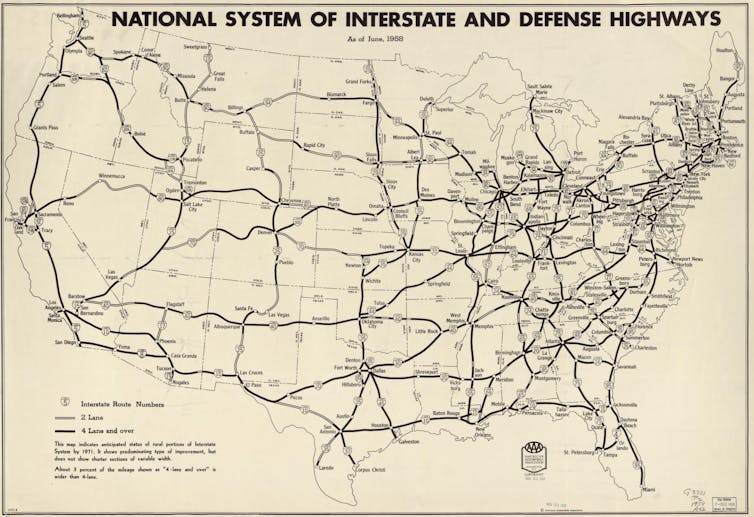

The UT team’s project seeks to enable county governments to improve land records throughout Appalachian Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia to pursue economic development opportunities more strategically as the communities shift away from coal mining as a primary industry.

Community and university partners include the University of Virginia at Wise, West Virginia University, East Tennessee Economic Development District, Appalachian Voices, the Livelihoods Knowledge Exchange Network, West Virginia Association of Geospatial Professionals, and the West Virginia Geologic and Economic Survey. They will collaboratively plan for regional land records infrastructure.

“Accurate and accessible parcel data is crucial for property tax systems that county governments depend on for disaster response planning and long-term economic development,” explained Shade, who officially joins the college on August 1. “Yet, high quality parcel data and geographic information systems require ongoing human and financial capacity, which are often lacking in hard hit coal impacted communities.”

The project team will host listening sessions to assess the training needs for local governments, identify existing resources and gaps at the county, district, and state levels, and better understand how industry and community stakeholders can use GIS data to meet their goals. The team will develop a plan from these sessions to help county-level partners train and use GIS to help sustain their communities.

Companion projects receiving ARISE grants include cybersecurity education by Marshall University Research Corporation, training for water-supply operators by the University of Kentucky Research Foundation, and a plan to increase affordable housing by the Federation of Appalachian Housing Enterprises.

“This round of ARC’s ARISE funding truly represents the forward momentum of Appalachia’s future,” said ARC Federal Co-Chair Gayle Manchin. “From growing workforce capacity in cybersecurity, to training workers in state-of-the-art geographical information systems, these projects ensure that Appalachians will be active participants in building a new era of opportunity across our region and the entire country.”

ARC is an economic development entity of the federal government and 13 state governments focusing on 423 counties across the Appalachian Region, with a mission to innovate, partner, and invest to build community capacity and strengthen economic growth in Appalachia to help the region achieve socioeconomic parity with the nation.