Katrina Stack Published in ‘The Conversation’

Gettysburg tells the story of more than a battle − the military park shows what national ‘reconciliation’ looked like for decades after the Civil War

Katrina Stack, University of Tennessee and Rebecca Sheehan, Oklahoma State University

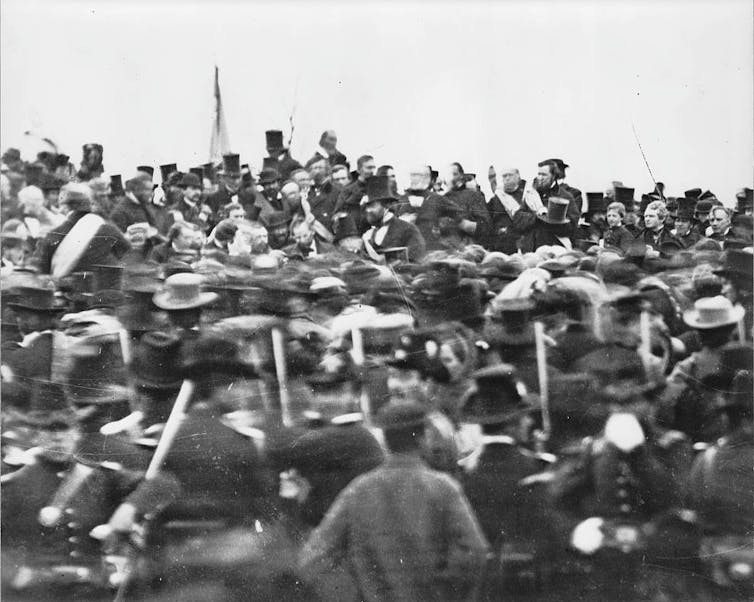

On Nov. 19, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, to dedicate a cemetery at the site of the bloodiest battle of the Civil War. Four months before, about 50,000 soldiers had been killed, wounded or captured at the Battle of Gettysburg, later seen as a turning point in the war.

In his now-famous address, Lincoln described the site as “a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that (their) nation might live,” and called on “us the living” to finish their work. In the 160 years since, 1,328 monuments and memorials have been erected at Gettysburg National Military Park – including one for each of the 11 Confederate states.

Confederate memorials in the American South have attracted scrutiny for years. In October 2023, a statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee was melted down in Charlottesville, Virginia, six years after plans to remove it spurred the violent “Unite the Right” rally.

Gettysburg has received relatively little attention, yet it occupies a unique space in these debates. The battlefield is one of the most hallowed historic sites in the country, and, unlike other areas with memorials to Confederate soldiers, is located in the North. The military park’s history offers a window into the United States’ attitude toward postwar reconciliation – one often willing to overlook racial equality in the name of national and political unity.

The ‘Mecca of Reconciliation’

Today, Gettysburg draws nearly a million visitors each year. In addition to visiting the museum, visitors can drive or walk among the monuments and plaques that cover the landscape, dedicated to both Union and Confederate troops. There are markers that explain the events of the battle, as well as monuments dedicated to individual people, military units and states.

As with any war memorial, particularly for a civil war, Gettysburg commemorates an event whose survivors held dramatically different views of its meaning. In his book “Race and Reunion,” historian David Blight identifies three main narratives of the Civil War. One emphasizes the “nobility of the Confederate soldier” and cause, while another focuses on the emancipation of slaves. The third is the “reconciliationist” view, with the notion that “all in the war were brave and true,” regardless of which side they fought for.

We are cultural geographers who study commemorative landscapes, with a focus on issues of race and memory. In our view, Gettysburg is a prime example of that reconciliation narrative: a site that aims to reconcile the North and the South more than it addresses the racial motivations of the conflict. The park’s own administrative history refers to Gettysburg as an “American Mecca of Reconciliation.”

No praise, no blame

From 1864 until 1895, the battlefield was under the administration of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, which placed markers along military units’ battle lines.

Starting in 1890, the U.S. War Department began actively preserving Civil War battlefields. Congress approved the creation of a commission of Union and Confederate veterans to mark the armies’ positions at Gettysburg with tablets that each bore “a brief historical legend, compiled without praise and without censure.” These policies were also included in the Regulations for the National Military Parks, published in 1915.

This guiding idea – “without praise and without censure” – was also evident at ceremonies for the battle’s 50th anniversary in 1913. Reconciliation was central in speeches and formal photographs, many featuring elderly veterans from both sides shaking hands.

At the time, there were no monuments to Confederate states; most markers, both for Union and Confederate troops, were for individual battle units.

State memorials

In 1912, the Virginia Gettysburg Commission had submitted plans for an equestrian statue of General Lee and other figures, with an inscription saying the state’s sons “fought for the faith of their fathers.” The chairman of the Gettysburg National Park Commission, however, had warned that such a statue would likely not be approved by the War Department because “inscriptions should be without ‘censure, praise or blame.‘” The chairman said that while “they fought for the faith of their fathers” might be true for Virginians, “it certainly opens the inscription to not a little adverse criticism.”

Eventually, the state commission agreed to inscribe simply, “Virginia to her sons at Gettysburg” – creating the first Confederate state monument.

But enforcement of the no praise, no blame policy was uneven.

Efforts to erect a monument for Mississippi, for example, began in the early 1960s. The state commission’s intended inscription read:

On this ground our brave sires fought for their righteous cause

Here, in glory, sleep those who gave to it their lives

To valor they gave new dimensions of courage

To duty, its noblest fulfillment

To posterity, the sacred heritage of honor.

The park superintendent pointed to two objections, however: first to the use of “righteous” and second to “here,” since Southern soldiers’ bodies were mostly relocated after the battle.

Mississippi Supreme Court Judge Thomas Brady, who collaborated on the inscription, wrote to the monument commission expressing his frustration over the objection to the “righteous cause” language. Even the “South’s most bitter critics … never questioned that the South felt that its cause was righteous,” he noted.

“The South has had the most to forgive in this matter and the South has forgiven,” Brady wrote. “Let us hope that the North has done likewise.”

In late 1970, a new superintendent was put in place at Gettysburg. Mississippi’s commission asked him to revisit the “righteous cause” wording – and expressed “genuine pleasure” that the new superintendent was a fellow Mississippian.

The monument was dedicated in 1973, with the “righteous cause” language included in its inscription.

‘Unfinished work’

From the start, the policies for monuments at Gettysburg called for a commemorative landscape that would recall the actions of those who fought and died on the battlefield. In reality, several monuments scattered over the landscape perpetuate the Lost Cause myth, which argues that the Confederate states’ chief goal was simply to protect the sanctity of state rights – whitewashing the atrocities of slavery and romanticizing the antebellum South.

In recent decades, however, the park has begun to do more to emphasize slavery in its historical exhibits and descriptions.

National Park management policy treats commemorative works as historic features reflecting “the knowledge, attitudes, and tastes of the persons who designed and placed them.” As a result, the monuments cannot be “altered, relocated, obscured, or removed, even when they are deemed inaccurate or incompatible with prevailing present-day values.”

The Gettysburg website notes that legislation and compliance with federal laws would be required to move many monuments.

When Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg, he called for Americans to dedicate themselves “to the unfinished work” of the Union dead, and to dedicate a portion of the battlefield to their memory. A century and a half later, however, the site also illustrates a messy postwar debate: the U.S.’s struggle to reconcile sharply opposed understandings of the Civil War.

This article has been updated to correct information about casualties at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Katrina Stack, PhD Student, University of Tennessee and Rebecca Sheehan, Professor of Geography, Oklahoma State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.