Alderman Published in The Conversation

Alderman Published in The Conversation

How a 2013 US Supreme Court ruling enabled states to enact election laws without federal approval

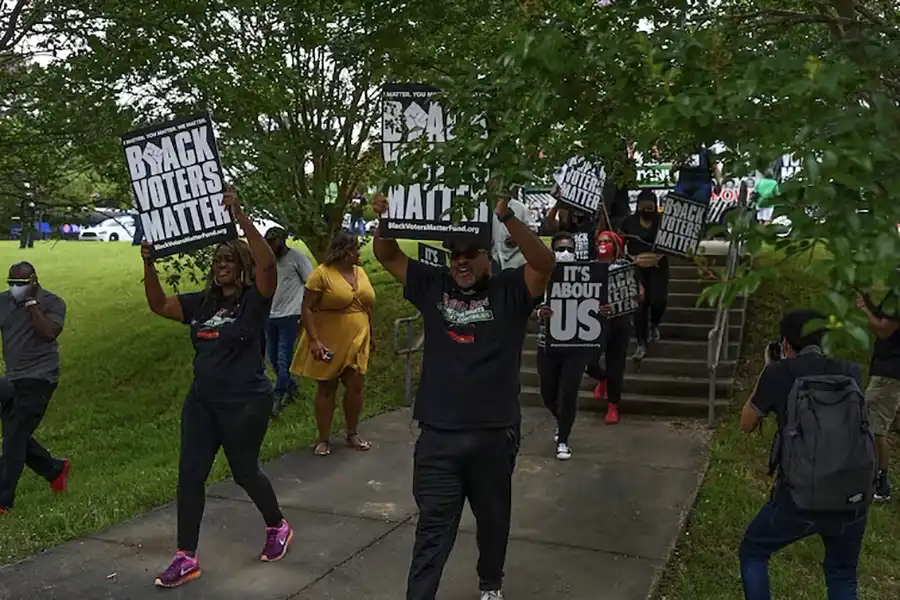

Josh Ritchie for The Washington Post via Getty Images

Joshua F.J. Inwood, Penn State and Derek H. Alderman, University of Tennessee

Since 2019, legislators and election officials in Florida have revised, passed and enforced restrictive voting laws that make it harder for poor people, former felons and people of color – who traditionally favor Democrats in elections – to vote.

At the same time, they appear to have taken exceptional measures that have made it easier for voters in Republican areas of the state to cast their ballots, especially after a natural disaster.

The pattern of favoring GOP voters and discriminating against people of color, especially against Blacks, has been so obvious that, in a brief filed in federal court on Aug. 17, 2022, federal prosecutors argued that Republicans lawmakers targeted Black voters when they enacted the new election law in Florida, a charge denied by lawyers defending the state.

Yet less than a week after the filing, instead of addressing widespread concerns over the restriction of voting rights, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis held a news conference to show how his state is taking “voter fraud” seriously.

Despite the lack of evidence of widespread voter fraud, DeSantis told the assembled media that the state’s new Office of Election Crimes and Security was in the process of arresting 20 Florida residents for allegedly committing voting fraud.

Based on media reports, the majority of those pursued by authorities were Black voters.

Although a judge dismissed charges filed against one man, we believe these arrests are a bellwether of more efforts Americans will likely see to intimidate voters under the guise of election security.

The question, then, is how are states allowed to enact election laws that appear race neutral – but have a disproportionate impact on voters who have been historically disenfranchised?

Impact of Shelby v. Holder

We are scholars of the American civil rights movement and the role of geography and voter intimidation in the long struggle for Black voting rights.

The actions in Florida are part of a national trend that saw dozens of states across the country overhaul their election laws after former President Donald Trump’s persistent and false claims of fraud in the 2020 presidential election.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

The rash of new state election laws includes everything from closing polling places to restricting the time and place of early voting. They also include partial bans on providing water and food to people standing in line to vote.

Not all of these laws included restrictions, and some were established to avoid health risks during the COVID pandemic.

These bills were often couched in the language of preventing voter fraud to protect democracy. “Voter confidence in the integrity of our elections is essential to maintaining a democratic form of government,” said Florida’s Republican Senate president, Wilton Simpson.

But voting rights experts argue that instead of prohibiting election fraud, many of the new laws may make it harder for people to vote.

In the past, the 1965 Voting Rights Act included requirements that, in states that historically had discriminated against the right of Black people to vote, such major changes to election law would have sparked a review by the U.S. Department of Justice to determine whether they could take effect.

The loss of that federal oversight was made possible by a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court 5-4 decision in the case of Shelby v. Holder. That decision eliminated the oversight requirements of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

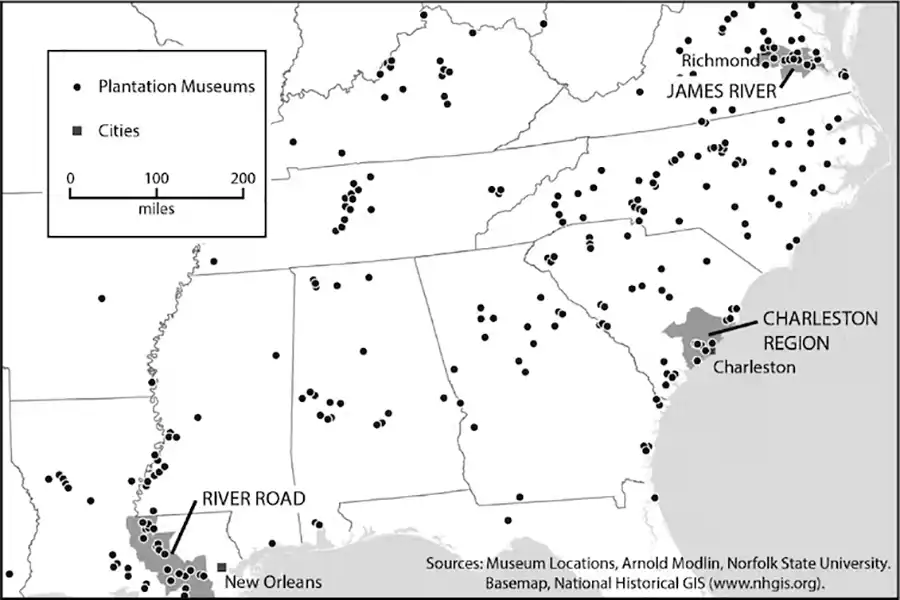

From the outset of the Voting Rights Act, Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina and Virginia were required to have federal oversight in order to prohibit those states’ adopting discriminatory election laws.

In addition, several specific counties in Arizona, Hawaii, Idaho and North Carolina were also found to have discriminated in the past, thus requiring federal oversight.

New state election laws

These states, long under scrutiny by the federal government for discriminatory voting laws, were some of the first states to enact new and more restrictive voting regulations and rules after the 2013 Supreme Court ruling.

Yet these states were not the only ones to consider changing or enacting new election laws since the 2020 presidential election. In 2022 the effort to restrict the right to vote has accelerated.

Thirty-four bills currently are moving through 11 state legislatures to restrict access to the vote. In all, 39 states have considered over 390 restrictive bills, and these efforts affect minority voters most specifically.

Though the impact on voter turnout is an open question among election experts, one thing is clear – the number of polling places and voting drop boxes in communities of color has diminished since before the COVID-19 pandemic.

While inconsistent data reporting makes it difficult to determine the exact number and location of closed polling places, recent statistics suggest that since the 2013 ruling, at least 750 voting locations in Texas, 320 in Arizona, 240 in Georgia, 126 in Louisiana, 96 in Mississippi and 72 in Alabama have closed.

Modern-day poll tax

In all, over 1,600 polling places have closed across the U.S. since the Holder decision in 2013.

Recently, civil rights organizations, including the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, have pressed Mississippi for information on poll closures in the state to determine if new election laws there are having a detrimental impact on Black residents’ ability to vote.

According to the Mississippi Free Press, the state “does not provide an up-to-date, comprehensive list or database of voting precincts to the public,” as required by law.

These closings, often done with little notice or public accountability, have occurred across communities of varying racial and demographic characteristics.

What unites these places across the country are the increased burdens and costs they impose on voters of color, older voters, rural voters, voters with disabilities and poor working people in general.

In our view, the poll closings since the Holder decision have created significant financial costs for those least able to bear them. We see the long lines as more than an inconvenience – they are effectively a modern-day poll tax.

Joshua Lott/The Washington Post via Getty Images

The poll tax was an amount of money each voter had to pay before being allowed to vote. After the Civil War, many Southern and Western states used the poll tax and other Jim Crow measures to keep poor and minority voters from being able to cast ballots.

The frequently exorbitant taxes were outlawed in 1964 by the the 24th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

Our research shows that democracy depends upon communities’ having equitable social and geographic access to voting places.

The new Florida election law was challenged in March 2022 by voting rights advocates, the League of Women Voters of Florida and the Florida NAACP. Though that case is under appeal – and restrictions were allowed to remain in place during the midterm election – Chief U.S. District Judge Mark Walker found in his lower court ruling that the Florida law placed restrictions on voters that were unconstitutional and discriminated against minority citizens.

“At some point, when the Florida Legislature passes law after law disproportionately burdening Black voters, this court can no longer accept that the effect is incidental,” Walker wrote.

Joshua F.J. Inwood, Professor of Geography and Senior Research Associate in the Rock Ethics Institute, Penn State and Derek H. Alderman, Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.